|

| d'Eon's entry in the St Pancras burial register |

The

counter-examinations and declarations of the two sets of Surgeons respecting the

sex of the late Chevalier d'Éon, reminds us of the examination of a well-known

blockhead at Cambridge for his degrees, who, as the last question was asked,

Whether the sun revolved round the Earth, the Earth round the Sun?” replied, as

the Chirurgical Gentry might perhaps, with more propriety have done—“Sometimes

the one, sometimes the other.”

Bristol Mirror - Saturday 02 June 1810

The body of the

late Chevalier d'Éon, was privately interred within the parish church of St.

Pancras, on Monday morning ; on the coffin was inscribed: - Charles Genevieve

Louis Auguste Andre Timothe d'Éon de Beaumont, ne 17 Octobre, 1727. mort. 21

Mai 1810." The Duke of Queensbury

allowed the Chevalier D'Eon an annuity of £50 to the day of his death.

Lancaster Gazette - Saturday 02 June 1810

In

1913, when Havelock Ellis, the great pioneering British sexologist, turned his

attention to transgender phenomena, needing a name for it but disliking the term

transvestism invented by his German

rival Magnus Hirschfield, he came up with the clumsy alternative sexo-aesthetic inversion. He soon

realised that his 23 letter 3 word rival to transvestite

was never going to catch on (“I’m just a sweet sexo-aesthetic invert, from

sexo-aesthetic invertual Transylvania….” The Rocky Horror Show has a lot to

thank Hirschfield for….). In 1920, casting around for a substitute, Ellis stumbled

upon the details of the 18th century career of Charles Genevieve de Beaumont, the

Chevalier d'Éon and came up with the much snappier Eonism. Unfortunately transvestite was by then too well

established to be dislodged even by a term coined in honour of perhaps the most

celebrated cross dresser ever (except, perhaps, for James Barry).

|

| The Chevalier as painted by Thomas Stewart |

Born

in 1728 in the pretty but sleepy Burgundian town of Tonnerre, the Chevalier d'Éon was the scion of

impoverished nobility, his father scraping a living as a royal official,

director of the king’s dominions, and eventually becoming Mayor of the

commune. He was a bright student who was

sent to study law in Paris when he was 15 and who eventually followed his

father into royal service by becoming a secretary to the intendant of Paris and

a royal censor of history and literature. He entered the shadowy world of

Bourbon espionage, the Secret du Roi, in

his late twenties and, by his own account (not always completely reliable) was

sent on a clandestine mission to the Empress Elizabeth in Russia. It was during

this episode that d'Éon first donned women’s clothing, disguising himself as

the Lea de Beaumont and passing

himself off as one of the Empress’ ladies-in-waiting. Louis XV awarded him 2000

livres for services rendered on his return to France where he temporarily hung

up his petticoats and cambric frocks and instead kitted himself out in a

dragoon’s uniform before setting off to fight in the seven years war. At the

end of that conflict the King dispatched him to London where he helped draft

the peace treaty and discovered a taste for the former enemy’s capital. A

reward of 6000 livres, the Order of St Louis, the title of Chevalier and the

post of chargé d'affaires at the London Embassy were d'Éon’s rewards this time.

He was clearly ambitious and acted as interim ambassador when the duc de

Nivernais was recalled to Paris, using the freedom from supervision to spy

privately for the King. When the Comte de Guerchy was appointed as the new

ambassador the humiliated d'Éon was promptly demoted to secretary. Seething with resentment d'Éon caused endless

trouble at the embassy and eventually received orders to return home. When he refused to obey orders the British

authorities were asked to extradite the stubborn secretary but they declined to

involve themselves in the dispute. When the French stopped paying his salary the

Chevalier retaliated by publishing reams of secret diplomatic correspondence

but taking care to keep back the most damaging documents (relating to potential

French invasion plans). The French suddenly became very cautious in their

dealings with d'Éon even when he commenced a lawsuit against the ambassador for

attempted murder. The lawsuit failed and the ambassador sued for libel; d'Éon

was declared an outlaw and forced to go into hiding. Eventually the French

Government reached an agreement with d'Éon, paying him a pension in return for

his silence over the secret documents.

Despite

strutting around town in a dragoon’s uniform it was in London that the first

rumours about his true sex began to circulate, rumours quite likely started by

the Chevalier himself. 18th century

gentlemen loved to bet and speculation regarding the Chevaliers true sex became

so rife that money started to be staked on the controversy. Amongst others the Stock Exchange started a

betting pool and the stakes were sometimes astronomical; one Da Costa bet Mr

Jones £700 guineas that the Chevalier was a woman. When Da Costa felt he had

sufficient evidence he demanded settlement of the bet but Wallace refused on

the grounds that the evidence was unconvincing (the evidence seemed to simply

be the word of other gentlemen ‘in the know’). The matter ended up in the

courts where Britain’s most senior judge, Lord Mansfield, had the pleasure of

hearing it. The jury found for Da Costa, effectively setting up a legal

judgement that the Chevalier was indeed a woman. Lord Mansfield was unhappy

with the verdict and encouraged a retrial at which he ruled that the contract

for the wager was ineffective because it was not made in good faith; his issue

was the matter of the Chevalier’s sex could not be resolved with a gross

indecency and intrusion on his privacy. But as far as the British public were

concerned d'Éon was now a woman. Astonishingly the Chevalier seemed to agree;

it was from this period that he cast aside the dragoon’s uniform and started

dressing and living as a woman, initially in France where he had returned in

1777 only to find himself effectively under house arrest at the family estate

in Tonnerre. In France he claimed to have been born a girl and been forced by

his family, who were concerned that a female heir could not inherit the estate,

to pass as a male. He also claimed that the new king of France Louis XVI

accepted this story but only allowed him to retain the privileges of a male if

he wore women’s clothes. One memoirist later wrote that “the desire to see his native land once more determined him to submit to

the condition, but he revenged himself by combining the long train of his gown

and the three deep ruffles on his sleeves with the attitude and conversation of

a grenadier, which made him very disagreeable company.” In 1779 d'Éon published La Vie Militaire, politique, et privée de Mademoiselle d'Éon and

began petitioning to be allowed to return to England. He was only granted the

right to leave France and return to London in 1785. The 1789 revolution ended d'Éon’s

royal pension and he lived in straitened circumstances in England until his

death ending up in debtor’s prison at least once. He earned a living by taking

part in fencing tournaments dressed as a woman, a sight unusual enough to

guarantee sizeable crowds of punters willing to pay for the privilege.

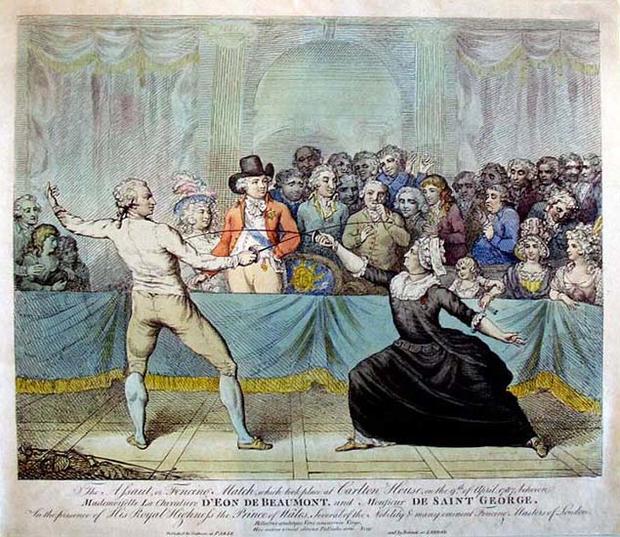

|

| "The Assault or Fencing Match which took place at Carton House on the 9th of April 1787" |

In

his final years the Chevalier lived with

an elderly widow, Mrs Cole, at her house in Millman Street, a thoroughfare

lined with small terraced houses mainly occupied by artisans and jobbing

craftsmen a short walk due south from Coram Fields and the Foundling

Hospital. The Chevalier was paralysed

through illness for four years before he died on Monday 21 May 1810. Mrs Cole

claimed to be astonished when she came to lay out her friends body because she

had never, not even for a second, suspected that he might be a man. What she

discovered on lifting the dead woman’s nightdress so disturbed her that she immediately

alerted the medical fraternity. On Wednesday 23 May in the tiny bedroom of the long

since demolished house a group of smartly dressed men gathered around the bed

on which lay the corpse of the 83 year old French (wo)man. They were a

distinguished assembly, mainly but not exclusively medical men but all ‘persons

of consideration’ according to newspaper reports. The group of at least 11

persons included Francis Seymour-Conway, the Earl of Yarmouth and member of

parliament for Lisburn, Rear admiral Sir Sidney Smith, Marie-Vincent

Talochon (‘Le père Elisée’), a 57 year old French émigré and former surgeon to Louis XVI who had attended d'Éon in

his last illness, Mr. Wilson, a

Professor of-Anatomy, Mr Ring and Mr

Burton, two respectable surgeons, Mr. Hoskins, a respectable solicitor, Mr.

Richardson, bookseller of Cornhill, the Hon. Mr. Lyttleton, Mr. Douglas, and a Mr Adair. Holding onto a corner of the

bedclothes was an up and coming member of the Royal College of Surgeons, Thomas

Copeland who had just celebrated his 29th birthday and, despite being back less

than a year from Spain where he did a stint as an army surgeon during the

Peninsular War, had already published the well received study Observations on some of the principal

Diseases of the Rectum. The group

watched in silence as Copeland pulled back the bedclothes and then, after

pausing to glance around the room, slowly exposed d'Éon thighs and pudenda. The lifted nightgown revealed withered thighs,

a rather distended belly and, nestling between them, a perfectly formed set of

male genitalia. A group of well bred British gentlemen would never do anything

as vulgar as gasp in astonishment and so the assembly had to content itself

with conveying their surprise by the furious raising of quizzical eyebrows.

In

a signed statement about the examination appended to a drawing of d'Éon’s cock

and balls Copeland later wrote “I hereby certify, that I have inspected and

dissected the body of the Chevalier D'Eon, in the presence of Mr. Adair, Mr.

Wilson and Le Pere Elizie and have found the male organ in every respect

perfectly formed. (Signed) T. Copeland, Surgeon, Golden-square.” It seems the medical men were not content with

just outward observation of this astonishing phenomenon; it was cut and sliced

open with scalpel and scissors until learned opinion was certain that they were

not dealing with something that merely resembled the male sexual organs but the

genuine thing. Perhaps there was some disappointment; no doubt at least a few

of the company would have been hoping for something more remarkable than an old

lady who turned out to be a man, at the very least a hermaphrodite.

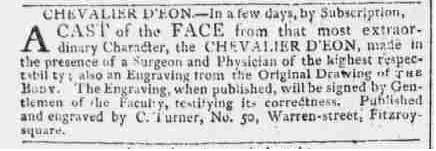

|

| Charles Turner's drawing of the Chevalier's profile based on the death mask |

The

following day Copeland was back at Millman Street bringing with him the

Professor of Anatomy at the Duke of York’s Hospital, Joseph Constantine Carpue and

a draughtsman Charles Turner. While Carpue examined the old lady’s corpse

Turner set about drawing the view between her flaccid thighs and also making a

death mask. Turner’s final drawing shows circumcised penis and testicles intact

and without the least sign of dissection.

As Copeland signed this last draught with the declaration that he had

inspected and dissected the body and

dated it the previous day, then Turner, for whatever reason, decided not to

show this post mortem intervention of the surgeon and drew the body as he

imagined it would have looked before Copeland got to work with his scalpel.

Carpue added his own statement to the drawing – “In consequence of a note from

the above Gentleman (Copeland) I examined the Body which was a Male. The

original drawing was made by Mr C. Turner in my presence. Dean Street, Soho,

May 24th 1810.” These were not the last visitors to view the Chevalier’s corpse;

according to the Morning Chronicle ““the body has been inspected by nearly 80

other gentlemen”, while the Morning Herald claimed ‘hundreds’ had been to

Millman Street:

The body of this

extraordinary character has undergone not only the anatomical inspection of the

whole faculty, hut also many hundreds of the most distinguished Curiosi of the

metropolis. Strange to say, the female visitants have exceeded those of the

other sex as three to one. His Highness the Duke of Gloucester, and several

other persons of distinction, were among the latter. It lies in a handsome oak

coffin, covered with black cloth, and a black velvet cross on the lid, at the

house of Mrs. Cole, of New Millman-street, to whose benevolent kindness and

attention, the Chevalier was indebted for the principal comforts of his latter

days. A cast was taken from the face on Friday. It is proposed to inter the

body in St. Pancras Church-yard the day after tomorrow.

On

the following Monday, the 28th May, d'Éon was buried in a private plot at St

Pancras, the coffin plate stating his name as the Chevalier Charles Geneviève Louis

Auguste André Timothée d'Éon de Beaumont; the burial register giving his age as

81. The Morning Advertiser alleged that “some minutia of his mortal remnants

are said to have been clandestinely conveyed away, to decorate the cabinets the

Medical Virtuosi.” The insults to the Chevaliers memory did not end there; exactly

a fortnight later the Morning Chronicle carried an outrageous advertisement

announcing that a few days hence, by subscription, could be purchased a copy of

the death mask of the Chevalier “also an engraving from the Original drawing of

THE BODY. The Engraving, when published, will be signed by Gentlemen of the

Faculty, testifying its correctness. Published and engraved by C. Turner, No.

50 Warren-street, Fitzroy-square.”

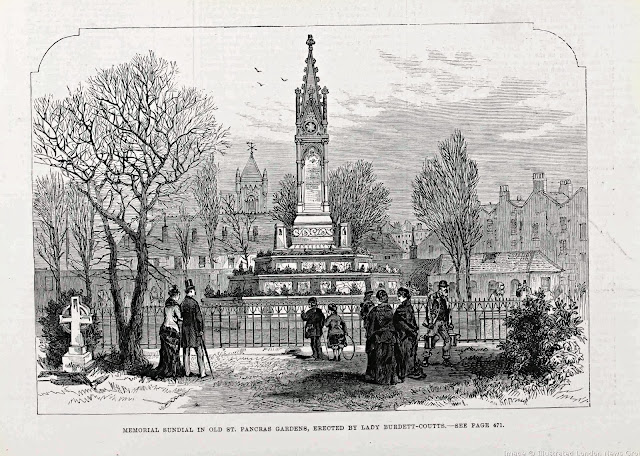

The Chevaliers grave was one of those later cleared to make way for St Pancras station and commemorated on the Burdett Coutts memorial.

The Chevaliers grave was one of those later cleared to make way for St Pancras station and commemorated on the Burdett Coutts memorial.

.jpg)