In the

observation ward of Claybury Hospital

I read the Coming

of the Bill.

Ivan

Blatný - Nastoupit v rad

|

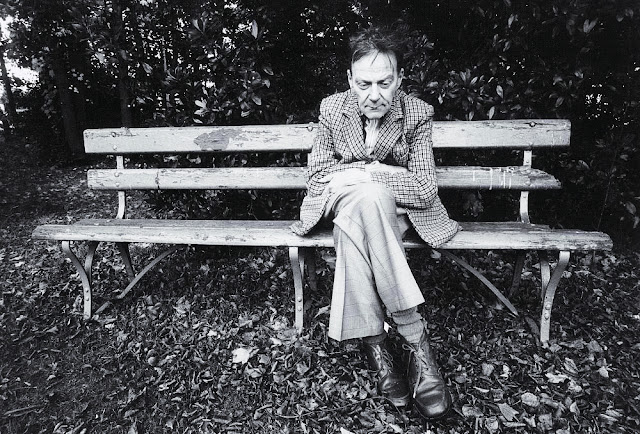

| A portrait of Blatny taken at Ipswich in the late 1980's by Jerry Bauer |

The

35 year old Ivan Blatný was admitted as a long term patient in 1954to Claybury Asylum in Woodford Bridge. The prematurely middle-aged Czech with the strong mittel-European

accent was in poor physical as well as mental health. He was thin, frail and undernourished, had a serious chest infection and was limping from an untreated

ingrown toenail. The psychiatrist who admitted him noted that the poet had been

brought into the hospital by friends on whose floor he had been sleeping for

the past few months. He had been making a precarious living for two or three

years working for the BBC World Service and Radio Free Europe and publishing a

few verses in an anthology of poets in exile. His homesickness and natural

timidity kept him isolated and he only mixed in the émigré community. As a

result of this and despite a natural facility for languages (he knew Esperanto,

German, Italian and Spanish as well as Czech) after six years in England his

spoken English still wasn’t fluent. It wasn’t his first stay in a mental

hospital – the doctor would have seen from his records that he had been

originally admitted to Friern-Barnet in 1948 and transferred later that same

year to Claybury. When the door of the ward closed behind him it was to be for

the last time, Ivan Blatný was never to live outside an institution again. He

spent the next 36 years living at Claybury and other hospitals in Essex and

East Anglia.

|

| The three year Ivan Blatny |

Ivan

was born in Brno in 1919 and came from an artistic background. He was

precociously intellectual and by the age of 9 he was entering into literary

contests and was learning Esperanto and German and travelling across Europe

with his parents. In 1930, when he was eleven, his father became ill with a

pulmonary infection that was eventually diagnosed as tuberculosis and died

shortly afterwards. The family were left in straitened circumstances but coped

until three years later when Ivan’s mother contacted hepatitis and also died.

The devastated Ivan moved in with his maternal grandparents and poured out his

feelings in verse. He later attended the Faculty of Arts at Masaryk University

reading Czech and German, for a few months in 1939 before the Nazi Reich Protectorate

closed down all places of higher learning.

With nothing better to do Ivan took over his grandfather’s opticians

business in the centre of Brno. For the next 6 years he devoted himself to

myopia, astigmatism and poetry. He contributed regularly to magazines and

published works written in collaboration with the Bohemian Jewish poet Jirí

Orten as well as three collections of his own poems. Jirí Orten was Ivan’s best

friend but on his 22 birthday, the 30th August 1941, he left his apartment in

Prague to buy cigarettes and was knocked down by a German ambulance. He was refused admission to the first

hospital he was taken too because he was Jewish and died two days later. The

stress of living under Nazism led to Ivan’s first breakdown for which he was

hospitalised briefly. In 1946 Ivan joined the Communist Party of

Czechoslovakia.

|

| Claybury Hospital, Woodford Bridge |

In

March 1948 the poet had a stroke of luck when he was offered a place on a three

man cultural delegation from the Czech Writer’s Syndicate to London. He

defected the moment he arrived in the UK, resigning his membership in the

Communist Party and his place in the Writer’s Syndicate and sending his

membership papers back to the respective organisations in the post. On the day

after his arrival he turned a talk he was scheduled to give on the Czech

service of BBC radio into a denunciation of the Communist authorities. The Czech authorities were furious and

reacted by declaring him a traitor, banning his work and confiscating his

property in Brno.

|

| Blatny in Brno as a young man |

Within a few months of his defection the

stress of living as a refugee and the virulence of the Czech authorities

reaction led to another breakdown. For

the next six years he was in and out of hospital; during periods of remission

he worked sporadically as an External co-worker for the BBC World Service and

Radio Free Europe, learnt Spanish and Italian and continued to write poetry.

But by 1954 when he was admitted to Claybury for the last time his illness

conspired to rob him of his poetic gift. He fell into a 15 year silence that

was to last until the late sixties. The young writer seemed to be totally

forgotten, his work banned in his homeland where many believed him to be dead

anyway, doubly locked away from the world, inside a profoundly disruptive

mental illness and inside the asylum, terrified of KGB spies amongst his

friends and acquaintances in the émigré community. His isolation seemed

complete. But at least one group of people still remembered him and still took

a keen interest in is welfare. When the archives of the Czech state security

services were opened following the velvet revolution there was a substantial

file on Blatný (codename NEWT) which included a top secret plan to bring him

back to Czechoslovakia. A Major Kolarik was to visit Blatný at Claybury and try

to entice him home. The visit was not a success; Major Kolarick informed the

Security Services that the poet was "in fact insane".

Following

this visit even the Czech State Security Services lost interest in him. For the

next eleven years Blatný lived quietly at Claybury with no contact with the

outside world. In February 1969 he received his first visitor from

Czechoslovakia since Major Kolarik. His cousin, Dr. Jan Šmarda had succeeded in

tracing him and visited him in secret. In June he received another visitor from

his hometown, a high school teacher, Vladimír Bařina. Bařina was an admirer of

Blatný’s work who brought news from Brno, greetings from some of his old

friends and poems from Klement Bochořák. The visit and the interest shown in

his poetry seems to have stimulated him to start writing again.

Over

the next eight years he wrote continuously, both in Czech and English and

guarded his manuscript’s jealously in a cardboard box. The hospital staff still

regarded his work as the scribblings of a lunatic and threw them away if they

were given the opportunity. This work would no doubt have all been lost in time

if Blatný had not been transferred in January 1977 to St Clement’s Hospital in

Ipswich. A nurse working at the hospital, Frances Meacham, visited Brno later

that year to stay with a friend who had served with her in the RAF medical

corps during the Second World War.

During her visit she met, by complete coincidence, Vladimír Bařina who

also introduced her to Jan Šmarda. The pair begged her to take care of Blatný

and to keep them informed of how the poet was. With this began an extraordinary

collaboration between the nurse and the patient that lasted until Blatný’s

death in 1990.

Frances

Meacham encouraged Blatný to put together a collection of his writings and she

sent these to the famous Czech novelist Josef Skvorecky in Toronto. In 1979

these were published as Stara Bydliste (Former Homes) by the Skvorecky’s famous

émigré publishing house 68. This was his first book for 32 years. Its success encouraged Ivan to put together

another book almost immediately which was published as samizdat in

Czechslovakia in 1982 and then again by the Skvorecky’s in 1987. Pomocná s˘kola

Bixley, Bixley Special School, was Blatný’s most unusual work, written almost as

much in English as in Czech with the odd dash of German, French and Esperanto.

|

| Blatny with Frances Meacham, 1980's |

Blatný

published no more after Pomocná s˘kola Bixley. In 1990 Vaclav Havel paid his

first official visit to the UK. Frances Meacham presented him with a letter

from Blatný offering him his congratulations and informing him that he will

remain in Britain. Five months later he became seriously ill with emphysema and

on the 5th August he died in Colchester General Hospital. Later that day the Czechoslovak ambassador

announced that Blatný was considered to be a Czechoslovak citizen at the time

of his death. Following the cremation of his body his ashes were flown back to

Brno and, in an official ceremony, they were placed alongside his father’s in

the Central Cemetery. Father and son rested side by side for the first time in

60 years.

On

the 28th October 1997 Vaclav Havel announced that the Za zasluhy medal for

merit would be awarded to Ivan Blatný in memoriam, “for outstanding artistic

work.”