Death of an

Eminent Botanist.—A remarkable man, Frederick Welwitsch, well known in

scientific, and especially botanical circles, died on Sunday afternoon, in

little lodging in Fitzroy Street, near Tottenham Court Road, London. The

deceased devoted his whole life to the flora of Africa. He was on the West

Coast of Africa for 18 years, in the service of the Portuguese, and was present

at the taking of Congo by them. He had collected, l am assured, forty thousand

specimens of African flora, and was at the time of his death engaged in a

"Magnum Opus" upon them. His lodging, which was almost entirely

filled with his specimens and books, so as hardly to admit of locomotion, was a

perfect sight. His best known work is on certain African molluscs.

Falkirk Herald - Thursday 24 October 1872

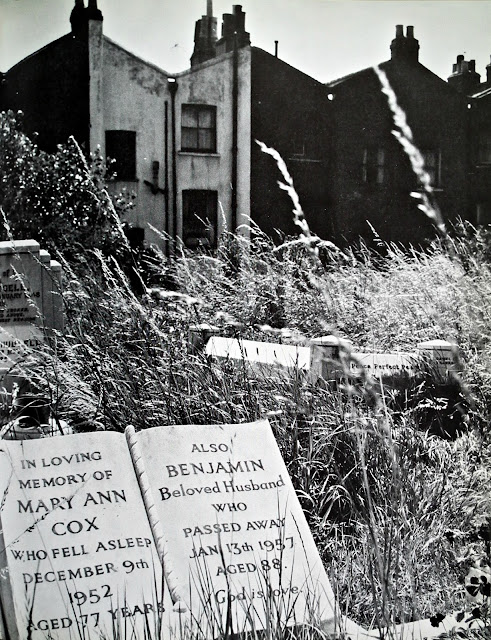

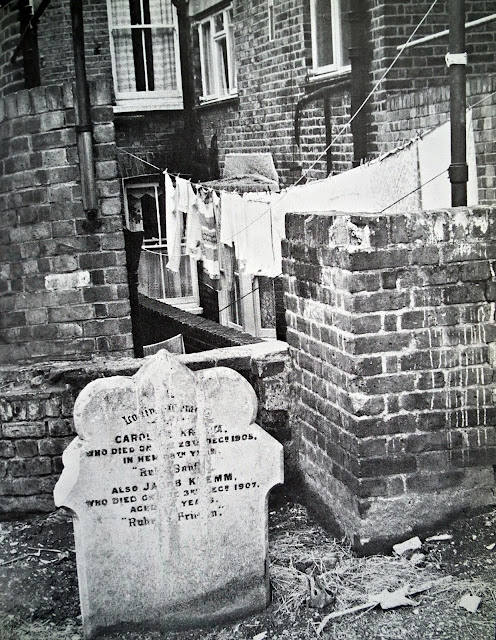

It

doesn’t matter how often I visit Kensal Green I always seem to be stumbling

across something new or unexpected, often in places I have walked past dozens

of times before. Just behind the main entrance on Harrow Road there is a gap

between the big memorials lining the verges, occupied by a relatively modest

memorial slab, which I often use to get off the path and explore the area

behind (which contains the distinctive red sandstone tomb of Daboda Dewanjee). Stepping across this conveniently low slab

for the umpteenth time I happened to glance down and found myself arrested in

mid stride by the name on the grave; Friedrich Welwitsch. Any doubts about his

identity were quickly dispelled by the Latin epitaph florae Angolensis investigatorum princeps. Much to my astonishment, because I had no idea

that he had any connection with London, I was looking at the final resting

place of the discoverer of that phantasmagorical plant of Namibia and the

southern Angolan desert, Welwitschia

mirabilis. Angolans, of which my wife is one, are inordinately proud of

their four national symbols, the Tchokwe sculpture known as O Pensador (the thinker) the Palanca

Negra (known as the Giant Sable

Antelope in the English speaking world), the Imbondeiro, the baobab tree, and Welwitschia, the improbable desert plant which has no English

name. Most Angolans are urban dwellers

and very few have seen the giant sable antelope or a baobab tree and even less

have had a reason to visit the almost uninhabited scorching deserts of the

south where they might see a Welwitschia.

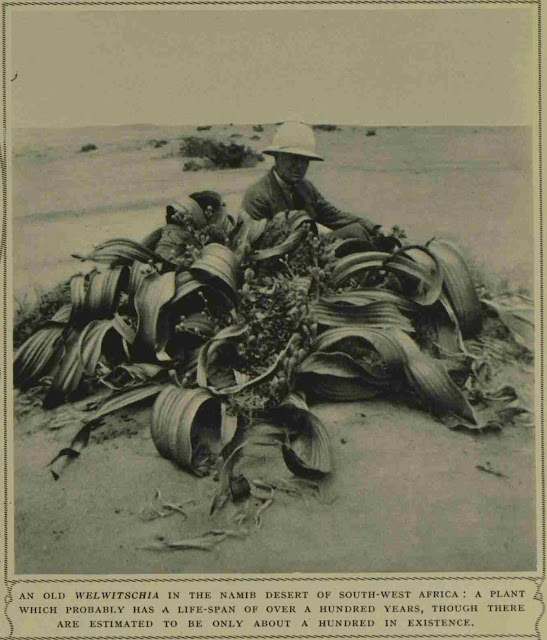

In

most photographs Welwitschia mirabilis

is rather scraggy and unappealing looking and it is difficult to understand why

anyone would give it a second glance. Friedrich Welwitsch’s entranced reaction

on first sighting seems due to a touch of sunstroke; “I could do nothing,” he

later recollected “but kneel down and gaze at it, half in fear lest a touch

should prove it a figment of the imagination”. Welwitschia may be an odd looking plant but its discoverer seems to

be overreacting. If you see a photo of the plant with a human being or, even

better for a large specimen, a four by four in it to give some idea the scale

you start to begin to get some idea of how impressively bizarre it is. In a

desert with virtually no plant life, no trees, few shrubs, little grass, barely

even any cacti, the sight of a writhing monstrosity just one and a half metres

high but almost 45 metres in circumference must be truly startling. Welwitschia is a living fossil that has

somehow managed to survive on a peripheral outpost of Gondwanaland whilst all

its contemporaries died out sometime in the Triassic. Individual plants can be

astonishingly ancient, many specimens would have germinated at the time of the

Norman Conquest and be due to celebrate their 1000th birthday in the next few

years and the oldest may well have been around since the time of Christ. The

untidy cluster of shredded leaves is deceptive, Welwitschia has only two leaves growing from a woody tap root that

reaches four or five metres in length, anchoring it almost immovably in the

friable desert soil. The plant seems to have a mass of leaves because the two

it has shred lengthwise in the harsh desert climate. The leaves are never shed,

they continue to grow for the entire life of the plant. The reason that it is

unusual for the leaves to reach more than four metres in length is that the

ever moving tips are abraded by the stony ground or nibbled at by iron toothed

herbivores. The Namibe desert has almost

zero rainfall and Welwitschia survives

on the coastal fogs that roll in most mornings from the Atlantic and are formed

when the deep, cold Benguela current meets warm shallow tropical waters. The Namibe desert is an almost unique

environment, nowhere else on earth will you see penguins rubbing shoulders with

hyenas, and the only other place on earth a transplanted Welwitschia

might survive would be in the Atacama in South America.

| Proof that Welwitschia is not carnivorous (photo courtesy of lusodinos blogspot) |

Friedrich

Welwitsch was born in the southern Austrian region of Carinthia in 1807 into

the large family of a prosperous farmer and surveyor who wanted his son to

become a lawyer. Welwitsch had other

ideas having been a keen amateur naturalist since his childhood and the

resulting conflict between him and his father led to stopping of his allowance

and Welwitsch switching from the law to

medicine for his degree in Vienna. He

did eventually make up with his father, after he had qualified as a physician,

but during his studies he supported himself by writing theatre reviews and

tutoring a nobleman’s son. He also continued with his botanical studies at the

Vienna Museum and began to look for opportunities to travel. One came, in a

timely fashion according to an early memoir of the naturalist, when “an act of

youthful indiscretion on his part, in the course of enjoying too freely the

gaieties of Vienna, rendered it expedient for him to leave Austria for a time”,

(his act of ‘youthful indiscretion’ was committed at the early age of 33). The opportunity came via the Unio Itineraria

of Wurtemburg, a learned society who sold shares in an expedition to the Azores

and Cape Verde Islands amongst their members at 24 florins each, each

shareholder being entitled to part of the specimens collected by Welwitsch. It

was a fateful opportunity, not only did Welwitsch make his lusophone

connections on this trip he also travelled via London and made the acquaintance

of the eminent botanist Robert Brown (also buried at Kensal Green a mere

stone’s throw away from Welwitsch).

Freidrich learned Portuguese in six weeks and so impressed his hosts

that he was offered a job looking after Lisbon’s Botanical Gardens. After

thoroughly studying the flora of the Alentejo and Algarve under the aegis of

the Portuguese government he travelled to Angola in 1853, stopping at Madeira,

Cabo Verde and Sierra Leone en route. He spent almost seven years in Angola,

initially in Luanda, exploring the coast and interior, before moving on to

jungles of Golungo Alto on the river Bengo where me met and lived with David

Livingstone for a couple of months. He later travelled to the south of the

country to Benguela on the coast and Mossamedes in the interior. It was here

that he discovered Welwitschia. He only returned to Lisbon in 1860 when a

native uprising of 1500 Ovimbundu left him trapped for two months in a

settlement near Huila. In 1863 the Portuguese Government gave him permission to

take his Angolan specimens to London, to consult with scientists who would help

with the work of identifying and classifying the collection. Once in London and

absorbed in his work he paid little heed to the increasingly insistent requests

of Portuguese officials for news on how the work was going. In 1866 his Portuguese

salary was stopped and Friedrich had to resort to selling duplicates from the

collection to pay his living expenses. This caused further fury in Portugal

where he was denounced in Parliament for selling off the Royal collections and

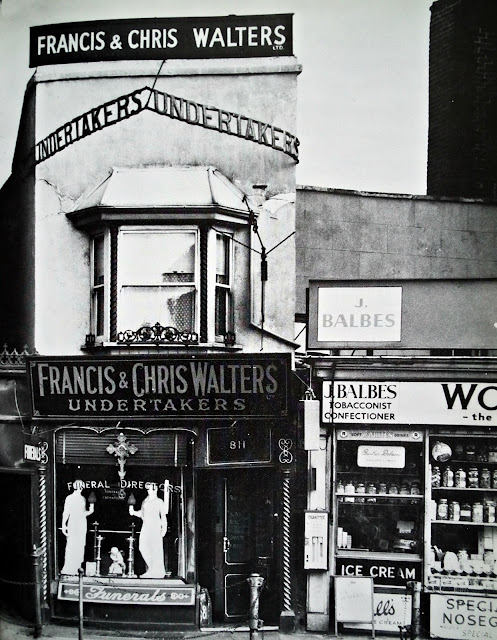

“living in splendour on the proceeds.” A fire at his lodgings at 15 Fitzroy

Street (just a ten minute walk from the British Museum) in the summer of 1872

did not damage his specimens but seems to have shaken him. His health rapidly

deteriorated and he died in his lodgings on the evening of 20th October 1872,

leaving a complicated will written just three days previously.

In

his will Welwitsch bequeathed his collections to a variety of institutions,

something that was bound to cause trouble when the Portuguese government felt

that they were the rightful owners. His first instruction was “my study copy of

African plants to be offered to the British Museum at the rate of E2 10s. per

century (100 species) subject to one set of Mosses being first selected

thereout and given to Mons. Duby of Geneva.” Two sets were then to go free to

the Portuguese Government, others to various herbaria including the Museum at

Carinthia, the Imperial Natural History Museum at Rio de Janeiro, the English

Government for the use of Kew Gardens, and to the Botanical Museums of Paris,

Berlin, Vienna, and Copenhagen and finally he bequeathed his general herbarium

and Portuguese herbarium at Lisbon to the Royal Academy of Sciences at Lisbon. Almost

as soon as the will went through probate the Portuguese Government, in the name

of King Luis I, started proceedings in Chancery try and wrest what they viewed

as their collection from the other legatees of Welwitsch’s will. The resulting

court battles took almost 3 years to settle.

On the 18th November 1875 the London Evening Standard was

able to report that a compromise between the litigant, the King of Portugal,

and the executors of Welwitsch’s will

had finally been reached after the court decided “that the King was entitled to

all the African collections; that he, as an act of grace and favour, should pay

to the defendants £700, in full settlement of all demands; that the study set,

next best set, be separated from the general collection by Drs. Hooker and Hiern;

that the British Museum should retain the second best set as a gift from the

King; that the defendants should hand over all the rest, of the collections to him;

and that the King should distribute the collections according to the will as an

act of grace and favour.” The best set

went of course to Lisbon but the British Museum did not have to pay the £2 10s

per 100 specimens stipulated in the will.

|

| Welwitsch probate record |

When

my wife was growing up in Benguela she and her primary school classmates were

convinced that Welwitschia was

carnivorous, why else would anyone make a huge fuss about such an ugly plant? They

imagined a single length of leaf as tough as nylon cord, snaking out from the

main body of the plant, creeping stealthily along the ground and soundlessly winding

itself around the ankle of a stray goat before hauling its bleating and

furiously struggling prey back to a hidden maw in the mass of leaves. Or maybe a

tightly coiled stalk would whip out to lasso a careless tribesman or foolish

white explorer around the neck and then drag its choking victim along the dusty

ground to be sucked dry. Angolans are great story tellers, as people living in

the grimmest situations often are. Rumour, exaggeration, gossip, boasting and

speculation transform even the most inconsequential incidents into flamboyant

narratives. As a result no one believes a word anyone else says if it sounds

even slightly out of the ordinary. When the country became independent in 1975

almost half a million white Portuguese hurriedly left Angola, many returning to

live in poverty in Portugal where they found themselves discriminated against

as retornados. Black Angolans started

to flee the country shortly after the colonists when independence degenerated

into a prolonged and bloody civil war.

|

| Namibe, Angola by Joost De Raeymaeker |

My

wife’s family left in the early 1980’s when the civil war was at its height.

The Portuguese were never especially welcoming to displaced Angolans of any

colour and the white retornados often

found they had more in common with the black refugees than they did with their

supposed countrymen. My wife’s family settled in a small village outside Lisbon

where they found themselves latched onto by a lonely middle-aged white woman

who had been born in Luanda. She had been brought up, she said, in colonial

splendour on a large coffee growing estate. Tia Maria, as they called her, missed

Africa and wanted to endlessly talk about her life there. There was a lot of

scepticism amongst her listeners about some of her stories. She claimed, for

example, that the family was so beloved by the workers on the estate that they

were surrounded by dozens of weeping Africans when they left to return to

Portugal in 1975. One of them was apparently so distraught at losing them that

he followed them to Luanda and to the airport where, in the confusion and chaos

as thousands of people fought to get on flights to Lisbon and Porto, he managed

to sneak onto the runway and hide in the wheel well of the aircraft taking the

family home by climbing the landing gear. He remained tucked away behind the

retracted wheel during the 8 hour, 3500 mile flight from Angola to Portugal. As

the plane began its descent towards Portela airport in Lisbon the crew extended

the landing gear, dislodging the unfortunate stowaway, who fell several

thousand feet and was killed instantly. The Angolan refugees listening to this

story snorted with disbelief; firstly, why would any black Angolan want to

follow his white mistress back to Portugal? The idea was simply ludicrous. And

secondly, even an idiot would know that it is not possible to stowaway beneath

a jet plane and survive a journey in the upper atmosphere where there is no

oxygen to breath and the temperature plummets to 50 or 60 degrees below

freezing. When my wife told me the story I agreed with her – it was ridiculous,

attempting to hitch a free plane ride in such a perilous way was unheard of.

After

dismissing the story we were astonished by the news in October 1996 that two brothers

from New Delhi had stowed away in the wheel well of a British Airways 747 on a

flight from New Delhi to Heathrow and one of them actually managed to survive

the flight. And then just a few months later, in March 1997, a 13 year old

Kenyan boy was found crushed by the landing gear on a flight arriving at

Heathrow from Nairobi. The following year a dead Azerbaijani fell out of the wheel

well of a British Airways flight from Baku when it landed at Gatwick. In the

following years there were more stories of planes landing with bodies in the

wheel well or of bodies falling from the sky as planes readied to land at

airports. Tia Maria’s story did not sound quite so far fetched any more,

especially when on a quiet Sunday morning in September 2012 British Airways

flight BA76 from Luanda flew over a deserted Portman Avenue in Mortlake at 7.42am.

Seconds later several residents of the suburban street were awoken by a loud

thud but when they looked out of their windows there was nothing unusual to see.

A few minutes later two boys on their way to church found an African man

dressed in jeans, white trainers and a grey hoodie lying dead on the pavement.

The police were called and initially suspected that the injuries sustained by

the unknown man were caused by a beating with baseball bats. But when a search

of the victim’s pockets showed that the only money he had on him were Angolan

Kwanzas and several witnesses came forward to say they had heard a loud noise

at a time that coincided with the time that the BA flight from Luanda passed

overhead, it began to seem more likely that the man was a stowaway. The victim

had no identification documents on him; the only clues to his identity were a tattoo

on his left arm with the letters Z and G and an e-fit reconstructed from the

remains of his battered face. The police hoped this would be enough for someone

in the British Angolan community to recognise him. It took police almost seven

months to identify him. In April 2013 they announced that the victim was José

Matada, believed to be from Mozambique, not Angola; ironically his 26th

birthday was on the 9th September, the day he had fallen from the

sky above Mortlake to his death in Portman Avenue. The Police had eventually

identified him via an Angolan Movicel SIM card retrieved from the smashed

mobile phone found in his pocket. This revealed a string of text messages

between him and a woman who was eventually traced to Switzerland. When the

police talked to her about the texts she was able to identify José, even

describing the tattoo on his arm. He had worked for the woman’s family as a

gardener and housekeeper in South Africa. When the family moved away José sent

her a stream of texts talking about going to Europe to make a better life for

himself presumably hoping she would help or offer him employment. He moved to

Angola from South Africa for reasons that have never become clear and made his

final, desperate attempt to get to Europe from Quatro de Fevereiro Internation

Airport in Luanda on the evening of Saturday 8th September. The pathologist

giving evidence at his inquest said that José would have been close to death,

possibly even already frozen and suffocated to death, by the time the BA Boeing

777 slowed to 240mph and dropped altitude to 2500 feet on its final descent to

Heathrow and he fell from the wheel well to the pavement of Portman Avenue,

SW14. The efforts of the authorities in Mozambique to identify José’s family

initially ended in failure but then in January 2014 they finally came forward

after seeing his story in the newspaper Verdade.

José’s body had been marked in an unmarked grave in Twickenham; his family

could not afford the $11,500 it would cost to repatriate him back home.

|

| E-fit of Jose Matada issued by the Police |