In the bed

directly opposite me a woman lies dying. An older woman. She’s whimpering

incessantly, trying to say something.

The nurses are trying to understand what she says. Earlier on she cried.

She lay quite still and the tears flowed from her closed eyes down her face. A

beautiful woman, fairly plump, cheeks a little pink, maybe she has a fever.

What does she think? Does she know she is dying? She seems to be conscious.

Then she certainly knows it. It is simply not something one cannot overlook. I

was not as far gone a few weeks ago, but still I knew exactly how things

looked....She is an Englishwoman so at least she is dying in her homeland. .......(Later, when the nurses

had moved screens around the dying woman’s bed) I think it is the end over there. It is difficult to think about

anything else. Now and then one hears laughter from the other end of the ward.

On the whole most are quiet, not depressed, although they too think of nothing

else it seems.

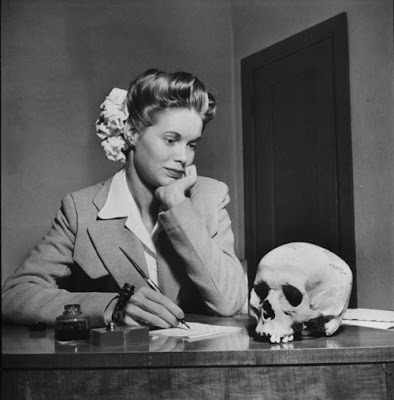

Dora

Diamant, Plaistow Hospital April 1951

At

53 Dora Diamant was hardly old but she knew she was dying. She had been

diagnosed with chronic nephritis, a condition which eventually causes kidney

failure and for which there was no known cure. The disease could have killed

her at any time; the only suggestion her doctors had to prolong her life was

bed rest and a strict diet with restricted salt and protein. Even then they

couldn’t tell her if she had years, months or just weeks to live. She was

almost frantic with worry about her seventeen year old daughter, a beautiful

but unworldly child who had spent most of her sheltered childhood in hospitals

and boarding schools and was so shy that she could barely bring herself to

speak to strangers. How would she cope with life without her mother to look

after her? Her other preoccupation were

her memories of her first lover, Franz Kafka. Death would erase them unless she

committed them to paper. On March 4 1951

in black ink , she wrote across the front cover of a bright red Silvine school

exercise book ‘To be given to Max Brod’. On the inside cover she wrote her

address ‘Ward Pasteur 1, Plaistow Hospital, E15’ (Dora lived in Finchley and so

can be excused not knowing Plaistow Hospital was in E13 not E15). In the blank pages of the exercise book she

took herself back to the summer of 1923 and the seaside town of Graal-Müritz on

the Baltic coast, the place where as a 25 year old volunteer at the Berlin Jewish

People’s holiday camp for refugee children, she had met and fallen in love with

Kafka.

|

| A young Dora Diamant, a photo taken in Berlin in the late 1920's |

Dora

Diamant was born on 04 March 1898 in Pabianice near Lodz in central Poland. When

she was 14 her mother died and her father Herschel remarried and moved the

family to Bedzin in Silesia, near the German Border, a town where he thrived as

a manufacturer of garters and suspenders. Although he was a successful, factory

owning business man, Herschel was a pious Hassid, a follower of the Rebbe of

Ger, R. Isaac Meir and his successors. Herschel was a learned man, he spoke

Polish and German as well as Yiddish and Hebrew and his house was full of books

in all four languages. Unlike their sons, who received only religious

instruction, the daughters of Hassidim were often allowed a secular education (considered

fit only to be wasted on girls) and so it was with Dora. When the teenage Dora

became rebellious and refused to marry, Herschel sent her away to Krakow to

study to be a kindergarten teacher. But

even Krakow was too provincial for her and without her father’s permission she

ran away to Berlin. Hershel recited Kaddish, the ritual prayer of mourning, for

his daughter and henceforth treated her as though she were dead.

In

1923 Dora volunteered to work for a Jewish charity which ran a holiday home for

refugee children at Graal-Müritz in Mecklenburg on the Baltic coast. One of the

other volunteers invited the almost unknown writer Franz Kafka, who was staying

at the resort with his sister and her two children, to a Sabbath dinner at the

camp. Dora had already glimpsed Kafka two days earlier, though at the time she

was not aware of who he was. She had seen a family on the beach, the handsome

father, as she assumed he was, sitting with his wife on covered beach chairs,

indulgently watching the two children playing in the sand. On the night Kafka

came to dinner Dora was in the kitchen cleaning and gutting fish, stripping off

their scales and removing their heads as well as their bloody entrails. She

recognised immediately the man from the beach when he stopped to talk to her;

“such tender hands and such bloody work they do,” were Kafka’s idea of small

talk. Dora soon learnt that the moody young writer (he remained eternally

young, even at the age of 40 which was how old he was when Dora met him) was

not in fact married and was staying in Graal-Müritz for three weeks with his

sister. Kafka returned to the camp everyday mainly it seems to see Dora and

very quickly passion blossomed between them in this unlikely setting. Dora

later remembered the highlights “Franz helping peel potatoes in the kitchen.

The night on the pier. On the bench in the Müritz woods.” Astonishingly in

those three weeks (given his chronic indecisiveness particularly in relation to

women) Franz came to a decision to leave his father’s house in Prague and move

in with Dora in Berlin. Perhaps Kafka’s new found determination was given spurs

by the knowledge that his tuberculosis was worsening and that he might not have

long to live.

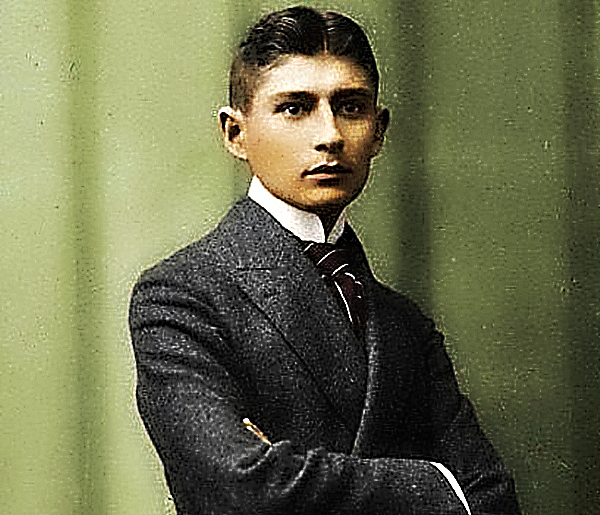

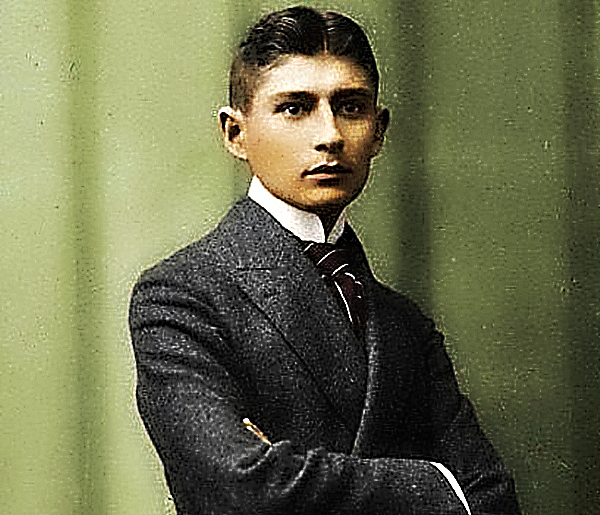

|

| Kafka in his 20's - 15 years before he met Dora |

By

September 1923 Kafka was in Berlin living in a small flat with Dora and working

on the stories that he would soon publish as “The Hunger Artist”. It was a

short lived idyll as Kafka grew increasingly sick over the winter of 1923/24. By

the spring of 1924 he was forced to return home to Prague leaving Dora,

temporarily, behind in Berlin. She joined him in Prague in April and

accompanied him to Dr Hoffman’s sanatorium at Kierling near Vienna. Only an

open topped car could be found for the journey and soon after they set off

driving rain set in. Dora devotedly stood over Kafka for almost the entire 330

kilometre trip holding an umbrella to try and keep him dry. She remained in

Kierling, visiting him every day until he died on the 3rd of June. She wasn’t

with him at his death, Kafka’s friend Robert Klopstock having sent her away on

an errand so that she didn’t have to witness the writer’s final agonies. TB had

made Kafka’s throat so painful and swollen that he could not swallow.

Ironically, given that he was working on correcting the proofs of “The Hunger

Artist”, he probably died of starvation.

Kafka

famously left explicit instructions that all his unpublished manuscripts were

to be destroyed after his death – he was confident that the few copies of his

books that had been sold would find oblivion unaided – and even more famously

his best friend and executor, Max Brod, after some agonised deliberation, not

only ignored the instruction to burn Kafka’s papers but went on to publish many

of them including all three of his novels. Dora was well aware of Kafka’s

wishes – she had helped him burn manuscripts while he was alive and had promised

him that she would do the same to the cache of notebooks and correspondence he left

with her. Like Brod she couldn’t bring herself to obliterate Kafka’s last

traces but unlike him she did not feel these should be shared with the rest of

the world. Brod knew she had many of Kafka’s final manuscripts but she lied to

him and told him that she had done what the writer had requested and destroyed

them. Brod believed her. For ten years the Kafka notebooks went with Dora

wherever she went. In 1933 they were with her when the Gestapo raided her

apartment; the notebooks were confiscated and never seen again.

After

Kafka’s death Dora’s life was swept into the maelstrom that was mittel European politics in the 20’s and

30’s. Back in Berlin, whilst working in the Yiddish theatre, she became a

committed Zionist and found herself drawn into radical politics. In 1932 she

married the editor of Die Rote Fahne (The

Red Flag), the communist party’s daily newspaper, Lutz Lask and two years gave

birth to their daughter Franziska Marianne (not only did Dora name her daughter

after Kafka, she brought her up to refer to him as her ‘other father’). As Nazi

control over Germany grew Lask fled to the Soviet Union where Dora joined him

in 1936. A year later Lask was arrested during the Stalinist purges and sent to

exile in Siberia. Dora lived with her mother in law in Yalta until the summer

of 1939 when she fled to England as a refugee, arriving shortly before Germany

invaded Poland in September. During the war she was detained for over a year as

an enemy alien in the Port Erin Detention Camp on the Isle of Man. When she was

released in 1942 she and Marianne returned to London where they lived in a

cramped flat in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead NW6 apart from a short spell

in Glenloch Road, Belsize Park when a bomb damaged Broadhurst Gardens. After

the war she dedicated herself to fighting the losing battle of preserving Eastern

European Yiddish culture alive in Whitechapel and was a founder member of the

group, The Friends of Yiddish with

the poet Abraham Stencl.

|

| Plaistow Hospital where Dora died in 1952 |

Dora

died of kidney failure in Plaistow Hospital in August 1952. She was buried in the

East Ham Jewish Cemetery in Marlow Road on August 18, an unseasonably wet and

cold day according to Marthe Robert, Kafka’s French translator, who was one of

the few people who attended the ceremony. “Dreadful

storms threatened England that day,” she later recalled, “black silhouettes

sank in puddles up to their ankles under icy cloud bursts. One could only move

forward by pulling hard on each leg to tear the feet away from the mud. The

rain had only faces to batter in this treeless and naked field, nothing but

faces already dripping wet, nothing but this face, next to me, streaked with

black from the dripping head-covering made of newspaper, handed out at the

cemetery door to serve as a hat. No writers or journalists attended her

funeral. The news had not reached them; only those with whom Dora had worked,

played and sang were now crying openly under the rain in the big East End

Jewish Cemetery.” Jewish custom dictates that no memorial can be placed

over a grave for at least a year; in Dora’s case it took 47, her headstone was

only erected in 1999 by a group of family descendents living in Israel none of whom

had known Dora personally. The inscription on her gravestone, “who knows Dora

knows what love means”, is a quotation from a letter written by Kafka’s friend

Robert Klopstock after the writers death, in which he described the devotion

shown by Dora to the dying writer. After her mother’s death, and despite the

best effort of Dora’s friends (who included George and Marianne Steiner)

Marianne became increasingly withdrawn and strange, eventually developing full

blown schizophrenia. In the worst crises of her illness, paranoid and distrustful

of everyone, she shunned other people including her mother’s friends who tried

to help her. She died alone in 1982, her badly decomposed body found by the

police in her flat after neighbours complained of the smell.

For more details of Dora's life see Kathi Diamant "Kafka's Last Love."